Honeyfiles

When an attacker gains initial access in a victim environment, one of the first things they look for are opportunities to escalate their privileges and move laterally. To do so, it’s common to search out sensitive files such as SSH keys, cloud credentials, and password manager vaults. As defenders we have one key advantage, we control our environments, and we can place traps and tripwires in adversary-targeted locations. One type of trap we can deploy are honeyfiles, closely monitored files which mimic the exact type of data adversaries are after. The moment a honeyfile is accessed an alert is triggered, tipping off defenders that something is awry.

Velociraptor

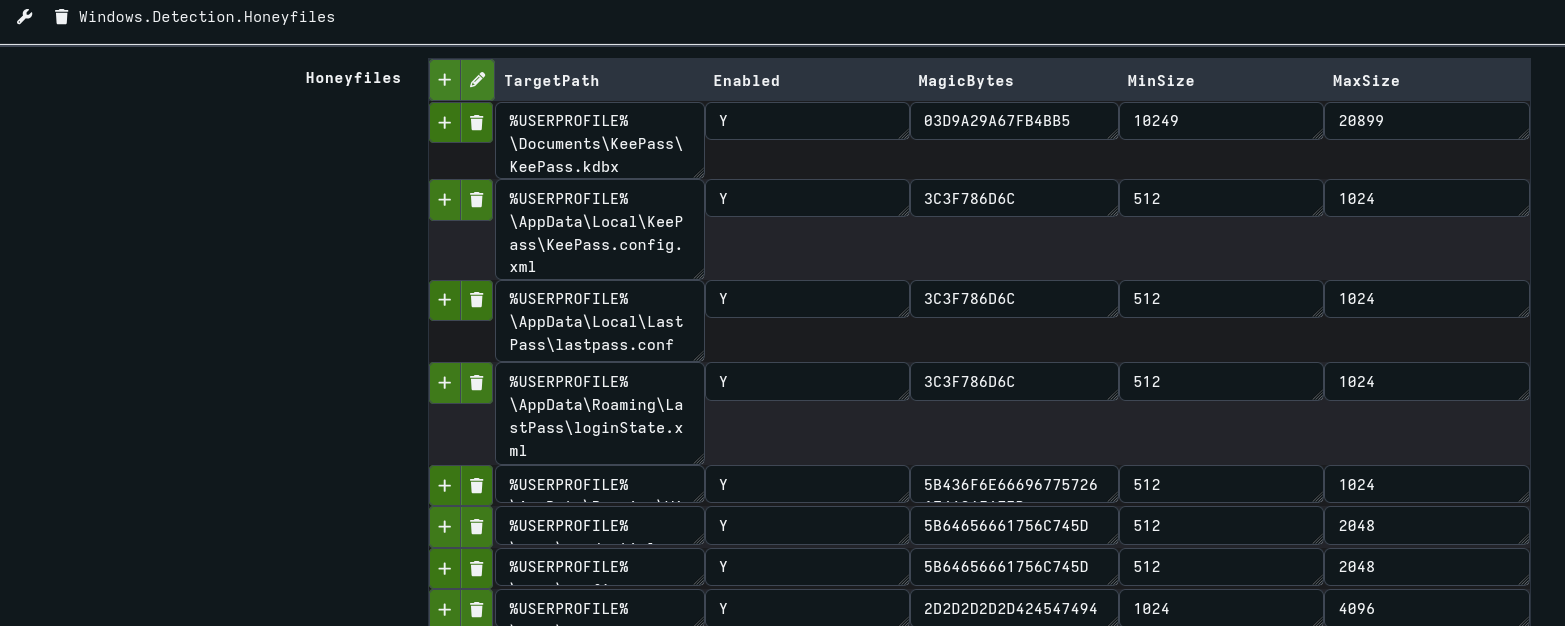

Traditional Windows honeyfile deployment consists of four steps: enabling file system auditing, creating decoy files, setting auditing ACLs, and monitoring event ID 4663. These manual steps make it difficult to scale across a fleet, and 4663 events lack much needed context. To solve these challenges, I co-authored a Velociraptor artifact with Matt Green which can create and monitor honeyfiles across multiple systems and users all in a single step. This allows defenders to rapidly deploy honeyfiles at scale and can be customized per environment to make them more enticing to threat actors.

We can deploy honeyfiles to all users, or specific users on the system, and configure the exact locations we’d like to deploy them to. Additionally, we can choose the starting bytes of the file to make it look more believable. Lastly, we pad the file with a random number of bytes so the size looks more convincing.

This artifact uses the ETW provider Microsoft-Windows-Kernel-File to watch file access, which in my testing has been the most reliable, performant way to do so on Windows. File access in Windows has always been tricky to monitor. It’s not captured by Sysmon, most EDR solutions don’t collect it due to its high volume, hooking function calls is out of scope unless we are writing our own agent, which practically only leaves 4663 events and ETW. Velociraptor is the perfect tool to tap into ETW at scale, and does the heavy lifting of filtering the firehose of data down to only the relevant events.

Honeyfiles are bound to trigger benign detections, so we need smart ways to filter these out. For example, it’s common for explorer.exe to trigger detections just by browsing to a folder, and other normal Windows processes like defrag can also trigger alerts. These represent just some of the noise you’re bound to face when deploying at scale. True positives will likely fall into two broad categories:

- Known executables with legitimate file paths used by attackers to read honeyfiles (PowerShell, cmd, Notepad, etc.).

- C2 frameworks and malware that have injected into trusted processes (Cobalt Strike, Sliver, Adaptix, etc.).

Known executables which shouldn’t access our honeyfiles for any legitimate reason are easy enough to detect, but what happens when a threat actor migrates their beacon into explorer.exe? How do we differentiate between this and normal activity?

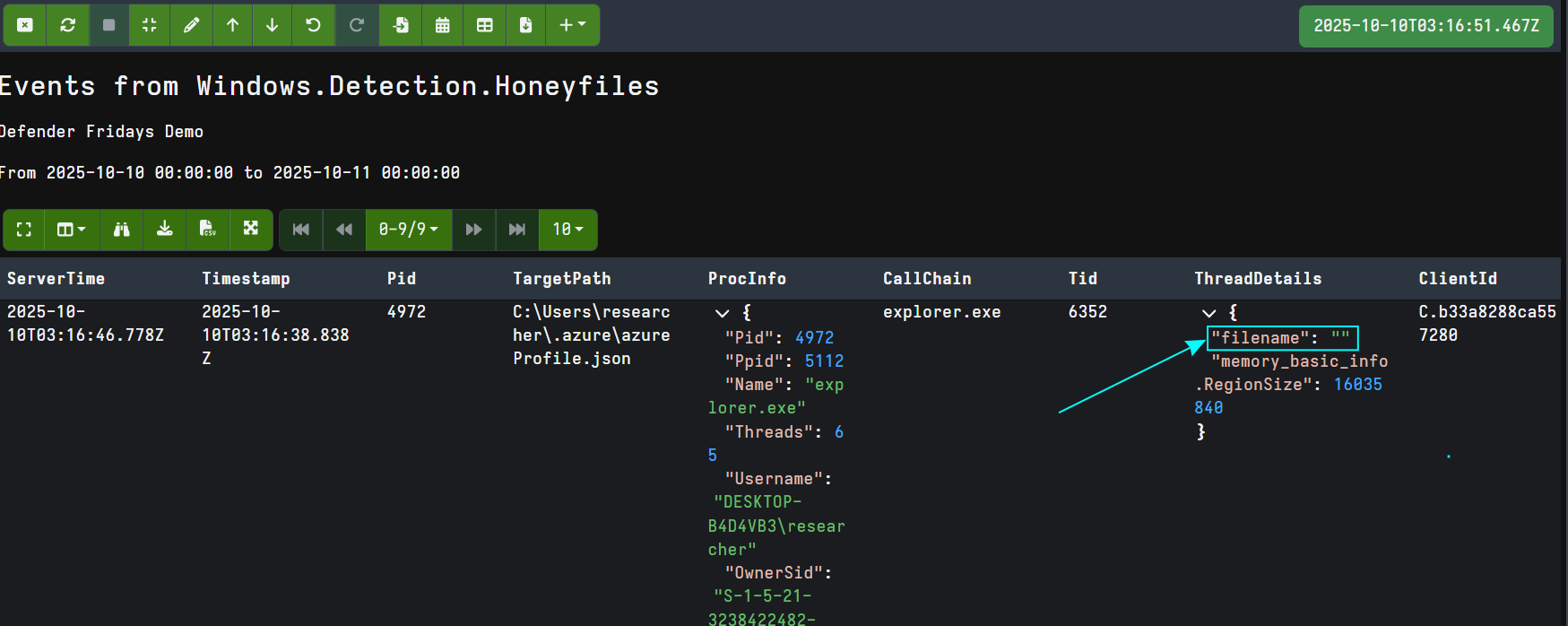

Microsoft-Windows-Kernel-File reports the thread within the process which accessed our honeyfile. We can pass this thread ID to the Velociraptor threads() plugin and check to see if the thread start address is located within an executable or DLL on disk. If it is not, we get an empty filename, raising suspicion.

Velociraptor checks if the thread start address is from a memory region marked MEM_IMAGE, and if it is, it returns the path of the image on disk. Most legitimate processes reading our honeyfiles should have a thread start address in a MEM_IMAGE memory region. If not, we’ll receive an empty filename from Velociraptor which is a strong indicator of process injection.

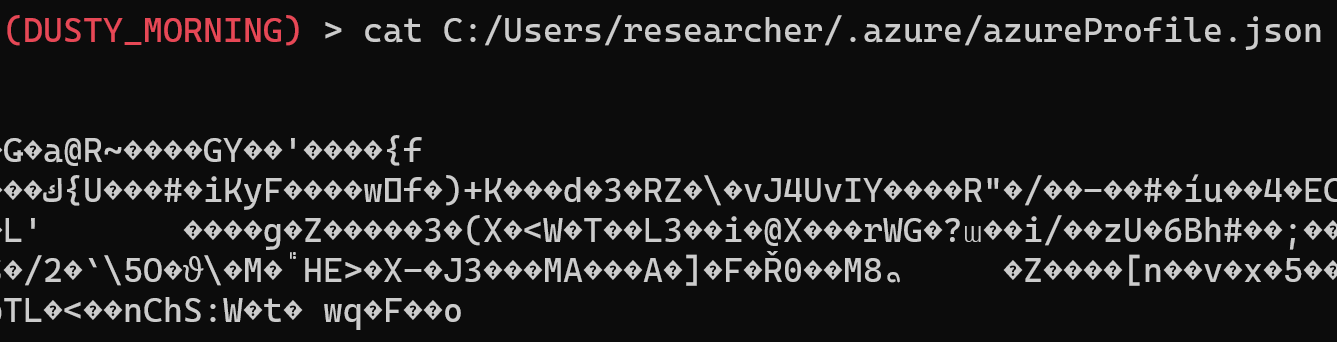

In the below example we test by running the popular C2 framework Sliver which is running inside an injected explorer.exe process. We then read the azureProfile.json file:

Velociraptor detects the access to the honeyfile, and furthermore returns an empty filename, pointing to process injection.

Attackers can spoof filenames to make it appear their code originates from legitimate disk-based modules through crafty process injection techniques, but this remains an effective indicator against many mainstream C2 frameworks and infostealers.

Linux Honeyfiles

While the Windows artifact leverages ETW for detection, I’ve also created a Linux variant that uses eBPF to monitor file access. This artifact works similarly to the Windows version, allowing deployment across user home directories with configurable honeyfile locations and realistic file characteristics.

The Linux artifact uses Velociraptor’s Tracee eBPF events as the data source, which provides low-overhead visibility into file operations. Like the Windows version, it can detect when processes access honeyfiles and enriches detections with process lineage and command-line arguments.

Linux environments, particularly servers, tend to have more predictable file access patterns than Windows systems. Servers are often purpose-built for specific workloads (a web server, database, or application) which means unexpected file access in user directories stands out more clearly. This makes the Linux variant especially valuable, as it has the potential to generate high fidelity detections with less tuning than the Windows counterpart. An attacker using tools like LinPEAS to enumerate SSH keys or cloud credentials will trigger alerts that are far less likely to be buried in benign activity.

Deployment Guidance

When deploying these artifacts, start slow. Every environment is different, and it’s critical to monitor both the performance impact on your endpoints and the volume of detections generated. Begin with a small subset of systems and users to establish a baseline.

I’ve done my best to tune this artifact and surface the most interesting information in detections, but to achieve high fidelity alerts you will need to customize and tune it for your specific environment. Pay attention to recurring benign processes that access your honeyfiles and adjust your filtering accordingly. The goal is to reduce noise while maintaining detection capability against genuine threats.

Bypasses

It’s also important that we understand the limitations of our detections. Honeyfiles are by no means a silver bullet, but should fit into a greater defense in depth strategy. Threat actors may use raw NTFS file reads using the MFT, or volume shadow copies to silently read our honeyfiles. They may also employ injection techniques that allow spoofing the filename of the running thread, making it appear legitimate when it is really injected code. Despite these bypasses, I still believe honeyfiles are worthwhile. Any time we can make a threat actor second guess something as simple as reading a file, that’s a win for defenders, and hopefully we force them to make mistakes or employ techniques that are detected by other controls.

Conclusion

As defenders we have the home turf advantage, we can prepare our environment using honeyfiles to detect even stealthy adversaries. Whether deployed through native auditing capabilities or Velociraptor’s advanced ETW monitoring, honeyfiles provide a low cost early warning system that catches attackers as they attempt to harvest credentials and other sensitive data.

The key to successful honeyfile deployment lies in strategic placement, realistic file characteristics, and intelligent false positive filtering. By leveraging thread analysis and process injection detection, we can distinguish between legitimate system activity and malicious behavior, making honeyfiles a powerful addition to any defense-in-depth strategy.

While attackers will continue to evolve their techniques, honeyfiles remain a cost-effective tripwire that forces adversaries to be more cautious and deliberate in their movements.